The American Heart Association’s 2024 Impact Goal -Addressing One Group at a Time: The High Maternal Mortality in American Indians and Alaskan Natives

Last Updated: November 26, 2024

The American Heart Association (AHA) created the 2024 impact goal before the pandemic, which has made healthcare disparities even starker.1,2 The goal was that by 2024, the AHA would help improve cardiovascular health for all and identify and remove barriers to healthcare access and quality.1 Healthcare disparities exist due to socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, and place of residence. What is not often discussed is the healthcare disparity that exists in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) individuals. The scientific statement led by Dr. Sharma is a much-needed review of the maternal cardiovascular health of this group. (Reference for the scientific statement paper)

Disaggregation of different groups of people can help distinguish groups that have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Precision medicine and medical models that take into account the impact of population-specific genetics, sociocultural, and physical environments may improve clinical outcomes.3 As a group, Asians were considered low-risk from atherosclerotic CVD, but when Asian groups were disaggregated, certain Asian groups, such as South Asians and Filipinos, were found to be at higher risk than Eastern Asian groups, such as Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans individuals.

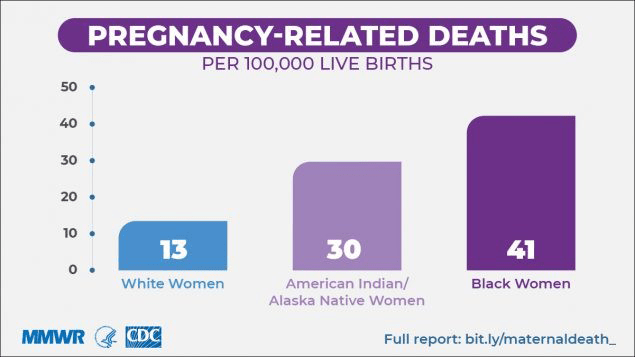

Sharma et al.summarized well the heartbreaking facts that, like African American women, maternal mortality is unacceptably high in American Indian and Alaska Native women. Much attention has been paid recently to the rising maternal mortality in the United States (US) since it was reported that the US had the highest maternal mortality rate of all industrialized countries.4,5 There has been much attention given to the highest-risk group, African American women, as shown in Figure 1. However, also shown in Figure 1 is that AI/AN women have the second highest risk of all the other racial and ethnic groups in the country.6 Sharma et al. also highlighted that in AI/AN pregnancy-related mortality, cardiomyopathy accounted for 14.5%. This was the highest of all the racial and ethnic groups (14.2% for Black and 10.2% for White women). Compared to White women, Black and AI women had a higher adjusted risk of developing peripartum cardiomyopathy (89% and 60% higher for Black and AI women, respectively).7 Possible mechanisms of peripartum cardiomyopathy include nutritional deficiencies, viral myocarditis, and autoimmune processes. Whether Black and AI women are at higher risk of these possible etiologies needs to be considered.{Davis, 2020 #11927} The factors besides ethnicity that predispose women to peripartum cardiomyopathy are multiple pregnancies, multiparity, pre-eclampsia family history, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, malnutrition, older age during pregnancy, and the prolonged use of tocolytic beta-agonists.{Bauersachs, 2019 #11922}

AI/AN women have the highest rate of risk factors for stroke. This high risk may be due to the misclassification of AI/AN ethnicity and non-representative sampling. AI/ANs were classified as non-Hispanic Whites and when this was corrected, the AI/ANs had After correction, it appears that their stroke mortality was among the highest of all racial and ethnic groups. AI/ANs had high rates of diabetes, obesity, hypertension, smoking, and physical inactivity.8 In addition, AI/AN women have a significantly higher likelihood of having gestational diabetes, developing infections, and postpartum hemorrhage than White women.9 Lastly, the scientific statement highlights that AI/AN have a higher prevalence of peripartum cardiomyopathy as the cause of maternal death than other racial and ethnic groups. Higher pregnancy-related death in the AI/AN population was observed over time across all age groups.6

The high risk for maternal mortality in AI/AN women is explained by the statement paper, which elaborated on the high prevalence of CVD risk factors and the social factors that can affect CVD outcomes. More than 60% of AI/AN women entering pregnancy have suboptimal cardiovascular health and this worsened between 2011 and 2019.10,11 AI/AN women have an age-adjusted prevalence of Type 2 diabetes, which is 3 times higher than White women which starts in childhood.12,13 The AI/AN women have a 45.5% prevalence of obesity.14 Cigarette smoking among AI women was as high as AI men (36.1% in men and 36.0% in women) and was much higher than the national median (19.6% in men and 16.8% in women).14

Unfortunately, only 60.4% of AI/AN women had prenatal care in the first trimester, much lower than the 81.6% of non-Hispanic White women. The reasons for the lower rate of prenatal care in AI/AN women include barriers in communication with physicians, lack of continuity of care, and sociodemographic barriers.The place of residence especially affected the maternal health of AI/AN women. Since 40% live in reservations, rural, or frontier communities this limited their access to health care.15,16

In addition to the high prevalence of CVD risk factors in AI/AN women, sociocultural influences weigh heavily on AI/AN women. The scientific statement pointed out that AI/AN women often experience racism and discrimination. There is unresolved grief, ongoing abuse, and mistreatment, all creating a setting for alcohol and illegal drug use, early onset depression, and anxiety. The environment of structural racism can lead to toxic stress that starts in childhood. Notably, AI/AN women have disproportionately high adverse childhood experience scores that can lead to high-risk behaviors and chronic diseases as adults. Compared to other racial/ethnic groups, AI/ANs had the highest frequencies in sexual and emotional abuse, family substance use, and witnessing intimate partner violence. 17

In addition, greater than 84% of AI/AN women have experienced some form of violence,18 of which includes sexual violence and physical violence.18 AI/AN women have homicide rates that are more than 10 times the national average in some counties. Overall these homicide rates are 2.8 times that of White women.19

The scientific statement acknowledges and calls for key stakeholders in government, public health, healthcare systems, and public policy to work on mitigating these disparities. The statement offers six strategies that can lead to improvement in maternal mortality and mitigating the risk of CVD in AI/AN women.

- Improve the education and competency of the health care professionals and address mental health and substance abuse rehabilitation.

- Enlist the help of women who hold traditional leadership roles since they can guide and implement effective heart health programs.

- Examine disaggregated data to accurately determine the leading cause(s) of AI/AN pregnancy-related deaths and design interventions to mitigate them.

- Use midwife-led care which can improve the quality of care and perinatal outcomes and improve delivery care coordination, home visits, and peer support in rural areas.16,20-22

- Improve preventive care, preconception counseling, and post-partum patient and family education on triggers and warning signs of CVD. Improve the early warning triggers of decompensation outlined in the AHA maternal health policy statement.23

- Address the disproportionate burden of CVD in AI/AN women by improving the understanding of clinicians, educators, and researchers about the culture and life experiences of AI/AN women.

Citation

Sharma G, Kelliher A, Deen J, Parker T, Hagerty T, Choi EE, DeFilippis EM, Harn K, Dempsey RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM; on behalf of the American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Underrepresented Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Hypertension; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Status of maternal cardiovascular health in American Indian and Alaska Native individuals: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association [published online May 31, 2023]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. doi: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000117

Science News Commentaries

-- The opinions expressed in this commentary are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association --

Pub Date: Wednesday, May 31, 2023

Author: Annabelle Santos Volgman, MD; Maria Isabel Planek, MD; Rupa M. Sanghani, MD

Affiliation: Rush University Medical Center